You are here

Zika Virus - Digital Media Kit

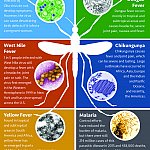

Virus Origins Health Impact NIH-Funded Research Funding for Zika Research Syndication Page Images Infographics B-Roll Soundbites

Virus Origins

Zika virus is a member of the virus family Flaviviridae. Other members of this family include dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile viruses. Zika virus is primarily transmitted to humans through the bite of infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The virus can also be transmitted through sexual intercourse or blood transfusion.

Zika virus was first identified in Uganda in 1947. In 2015, Brazil confirmed its first Zika virus infection, and since that time, countries and territories in the Americas and the Caribbean have experienced Zika virus transmission. Several U.S. territories and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico experienced widespread transmission. The first cases of locally transmitted Zika virus in the continental United States were confirmed in Miami, Florida in July 2016. Since then, local transmission has also been reported elsewhere in Florida as well as Brownsville and Hidalgo, Texas. Other cases in the continental United States have occurred in people infected during travel to areas where Zika virus is circulating. In addition, returning travelers infected with Zika have passed the virus on to their sexual partners.

In non-pregnant people, the virus is generally eliminated from the body after a few weeks although it may remain longer in semen. Most people who become infected with Zika virus do not become sick. For the less than 20 percent of people who do develop symptoms, the illness is generally mild and includes fever, rash, joint pain and conjunctivitis (red eyes). Illness lasts several days to a week.

Health Impact

One of the major public health threats posed by Zika is to pregnant women, who can pass the infection to their fetuses during pregnancy or possibly around the time of birth. This exposure to the virus can result in serious birth defects, including microcephaly. Microcephaly is a medical condition in which the circumference of the head is smaller than normal, often because the brain has not developed properly or has stopped growing. Depending on the severity, children with microcephaly may have impaired cognitive development and other brain or neurological abnormalities. With viral-induced brain injury, such as that caused by the Zika virus, there is often widespread tissue and cell death leading to brain shrinkage rather than simply impaired growth. One of the most concerning findings has been that of acquired microcephaly, where a child exposed to Zika in utero has a normal head size at birth, but develops microcephaly during the first year of life.

Zika can cause other congenital anomalies as well, and the cluster of findings has been termed congenital Zika syndrome(link is external) based on the following features:

- Fetal brain disruption sequence, an extreme form of microcephaly in which the fetal brain stops growing and the skull partially collapses

- Decreased brain tissue with a specific pattern of brain damage

- Damage to the back of the eye

- Arthrogryposis, or abnormal positioning of the limbs

- Hypertonia, an increase in muscle tone that makes arms and legs stiff and difficult to move

The virus has been associated with neuronal migration disorders, hydrocephalus (water on the brain), seizures, and behavioral anomalies. Zika infection can lead to miscarriage and stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, and problems with vision and hearing in affected infants. In fact, Zika virus is associated with retinal lesions in about a third of infants exposed in utero, often leading to blindness. Although long-term outcomes of Zika exposure are not fully known, researchers anticipate that there will be a spectrum of disorders, including developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, and motor abnormalities, as the children age.

In rare cases, most commonly in adults, Zika infection may also lead to Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune disorder in which damaged nerve cells or nerve structures cause partial or complete paralysis. Zika infection may also cause additional neurological complications, such as inflammation of the spinal cord, known as myelitis, and encephalitis, inflammation of the brain.

NIH-Funded Research

The National Institutes of Health supports a broad portfolio of research to improve understanding of Zika virus and how it spreads, the health effects of the virus, particularly on the developing fetus, and is developing diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics to better detect, prevent and treat infection.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is supporting basic research to better understand the Zika virus’ natural history and evolution, viral biology, structure, replication, transmission, and ability to cause disease as well as the virus’ interactions with mosquitoes and the human immune response to Zika. NIAID scientists have already created vaccine candidates for other flaviviruses that can be used as a starting point for a Zika vaccine. Currently, NIAID is developing multiple vaccine candidates to prevent Zika virus infection, more information on each vaccine.

The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) is also supporting research to identify potential small-molecule treatments for Zika virus infection. By using high-throughput drug screening, including both large-scale novel compound libraries and drug repurposing screens, researchers have identified compounds that potentially can be used to inhibit Zika virus replication and reduce its ability to kill brain cells.

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is supporting research to understand how Zika virus infection affects reproductive health, pregnancy, the placenta and the developing fetus. These studies aim to explain the virus’ impact, range of complications, long-term outcomes, and the health needs of children who were exposed to Zika virus in the womb. NICHD is also examining the potential risks that infection with Zika virus might pose for pregnancies already complicated by HIV and other co-infections.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is supporting research on microcephaly that looks at the genetic mechanisms of brain development, and fetal brain cells that are vulnerable to infection and how the infection causes brain malformation. NINDS also supports research on Guillain-Barré syndrome that focuses on identifying certain characteristics of some viruses and bacteria that activate the immune system inappropriately.

Funding for Zika Research

Zika virus does not have its own category in the NIH Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system. Reporters can search for unofficial funding information on Zika virus by conducting a key word search for active projects using NIH RePORTER. If you choose to use the data from your analysis in your story, please state that the numbers are unofficial estimates based on your analysis using NIH RePORTER.

In FY 2017 NIAID obligated $152 million in emergency supplemental funding appropriated by the Zika Response and Preparedness Act, 2017 (H.R. 5325). These funds supported new research and ongoing projects funded in FY 2016 using repurposed Ebola funds, the HHS Secretary’s transfer (which realigned funding from other NIH Institutes) and NIAID’s FY 2016 and FY 2017 appropriations.

Syndication Page

Zika virus-related information from across NIH is available on the syndication page.

Images

Infographics

B-roll

This page last reviewed on March 15, 2019